- Home

- Jody Lee Mott

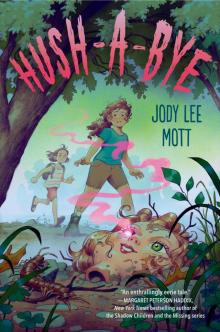

Hush-a-Bye

Hush-a-Bye Read online

VIKING

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC, New York

First published in the United States of America by Viking,

an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC, 2021

Copyright © 2021 by Jody Lee Mott

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Viking & colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Visit us online at penguinrandomhouse.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

Ebook ISBN 9780593206805

Cover art © 2021 by Matt Rockefeller

Cover design by Samira Iravani

Design by Jim Hoover, adapted for ebook by Michelle Quintero

This book is a work of fiction. Any references to historical events, real people, or real places are used fictitiously. Other names, characters, places, and events are products of the author’s imagination, and any resemblance to actual events or places or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

pid_prh_5.7.1_c0_r0

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Acknowledgments

About the Author

1

IT WAS DEEP in the afternoon of the last Tuesday of summer when I kicked away a willow branch lying on the riverbank and found the head.

My eyes had been closed. I’d been imagining, for no particular reason, how the September sun would look to the salamanders trolling the murky Susquehanna riverbed. Like margarine on burnt toast, I supposed. Then my foot knocked into the branch, my eyes opened, and another eye stared back at me.

Its yellow hair was tangled with twigs and muck and broken glass like some crazy bird’s nest. It had a scratched cheek, a chipped-up nose, and a grimy clot of mud in the hole where the left eye should have been. I picked up the head and held it by its ragged neck. The body, I supposed, had long since floated away.

“Poor little doll,” I said. “Where’d the rest of you go?”

I glanced behind me. My sister, Antonia, was somewhere along the slope above the bank, searching for flat rocks to skip on the water. She was always somewhere close by.

I bent down to drop the head back in the hollow space where it must have been hiding for weeks—maybe years, for all I knew. I wondered if the rest of her might be hiding somewhere on the small river island that sat a couple hundred feet out from where I stood. The curve of its shore matched the curve of the riverbank like a puzzle piece, and it was covered in tall birch trees that jostled against each other.

I looked at the river. Bars of light shivered across the surface. There hadn’t been a single cloud in the sky since the middle of August. Nothing above us but a wide sheet of blue.

Looking across ripples of sunlight on the river’s brown face, I wondered what would happen if I tossed the doll’s head into the water. I wanted to make the sunlight dancing there smash into a million pieces. Somehow, that seemed like the best possible thing I could do that day.

I weighed the doll’s head dangling from my hand, its hair twisted in my fingers. Its one good eye watched me. Almost like my daddy’s eyes—bright emerald green and full of mischief. At least, that’s how I remembered them.

I bit my lip and swallowed the sour ball of pain rising up my throat. The eye still looked at me, but it didn’t seem so bright anymore. It was dull and scratched and looked like nothing more than a cheap glass eye stuck in a poor broken doll’s head.

“Lucy?”

I turned. Antonia stood there with her hands cupped together, full of rocks too fat for anything but sinking with a loud plop. She was smiling, and her eyes were wide open even though she was facing into the sun. I could never understand how she was able to do that without squinting. The sparkly duckling barrette she’d worn since second grade glittered in the sunlight.

“Gross,” Antonia said, but she was still smiling. “What’s that?”

“Nothing,” I said. “Just an old doll’s head. Come look.”

Antonia dropped the rocks, letting them thump in the undergrowth, and shuffled toward me. I pressed my finger against the doll’s cheek.

“See?” I said. “Only an old broken doll’s head.” Antonia wrapped her hand around the head and tried to pull it toward her. I jerked it away.

“Stop that,” I said, a little more harshly than I’d intended. “There’s glass in its hair. You’ll cut yourself. I’m going to throw it back where I found it. Nothing but trash anyway.”

Antonia pouted. I tried to ignore her, but that pout always rankled me. Even though there was only a year’s difference between us, sometimes Antonia acted like such a baby. According to Mom, Antonia just had her own “Antonia way” of doing things, which meant she needed a little extra help at school, and a little more patience from me. I knew it wasn’t completely her fault why she acted the way she did, so I tried to be understanding. I didn’t always succeed.

I shook my head to break up the annoyed feeling. There were still a few more hours of this day to enjoy my freedom. No sense in ruining that with fussing over things I couldn’t change. And no sense in keeping some dirty, broken, good-for-nothing doll’s head.

I stepped toward the river and drew my arm back. A gust of wind shook the gray birch branches across the far bank. As they swayed, I thought I heard something—a faint voice whispering among the sound of rattling dry leaves.

Take me home.

I swung about and glared at my sister. “What did you say?”

Antonia cocked her head to one side. “I didn’t say nothing. Must have been the doll.”

I looked at my sister for a long time, then shook my head. “Don’t be silly.” I picked shards of glass out of the doll’s hair. Too many worries about school tomorrow were making me jumpy, making me hear things. I needed to settle myself down.

“It’s sad, though, don’t you think?” I said. “Poor thing left all alone here. Her little body’s probably washed all the way to China.”

“My teacher read a book about a glass bunny that got lost,” Antonia said. “He got drowned in the ocean until some fisherman pulled him out and saved him.”

“Probably shouldn’t throw her back in the river. That would be littering. We can put her in the trash when we get back home.”

Antonia l

eaned in and squinted at the doll’s head. “She’s not garbage,” she said. “She needs us. She’s lonely.” She rested her cheek on my arm. “Can’t we take her back to the trailer? We can fix her up, and maybe we can find another body for her.”

I nudged Antonia away. “Mom wouldn’t like it. She’s already threatened to take a shovel to all the junk under your bed.”

“It’s not junk,” Antonia said. “They’re my precious treasures.”

Her precious treasures were a flat soccer ball, a trunkless stuffed elephant named Mr. Lumps, a large bag full of knotted rubber bands, a papier-mâché Earth with only five continents, and about a hundred other bits and pieces she’d picked up here and there and shoved under her bed “for later.”

“She’d be the most precious treasure of all,” Antonia said. She nestled her cheek against my arm again and fluttered her eyelashes. “Please, can we keep her? Pretty please?”

I had to smile. She knew her eyelash flutter always worked on me. “I suppose so . . . if we don’t tell Mom.”

Antonia’s eyes grew wide. “You mean lie?”

The doll’s green eye glowed in the afternoon light, and the sound of the river filled our ears. A single cloud, thin as a whisper, floated just above the treetops.

“Not a lie.” I trailed my pinkie across the doll’s stubbed nose. “A secret. Our secret.”

2

I’D COME DOWN to the river almost every summer day since we moved to Oneega Valley, a long, narrow ribbon of town in New York State, just a few miles north of Pennsylvania. Antonia had found the dirt footpath hidden under a row of winterberry bushes running behind our trailer. You had to squeeze through them, shuffle sideways down the path to avoid the pricker bushes and stinging nettles that grew between the willows, then slide down a low slope to get to the riverbank.

Antonia had summer school, so I usually went alone. I’d sit on the bank under a willow tree for hours, watching the dragonflies dance across the water and the island’s birch trees nod in the wind. Dark columns poked up here and there between the pale gray trees like a giant’s fingers. I liked to imagine they were the remains of a long-forgotten meeting house of some secret society. I dreamed about visiting it one day to get a better look at those columns, but the river was too muddy for swimming, and we didn’t have a boat.

It was strange I’d never noticed the doll’s head all those days and weeks I’d spent there. Not until Antonia showed up, anyway. That figured. I mean, I liked her company, but things always got more complicated with her around. And now here we were heading back home, trying to sneak in a busted-up doll’s head.

After Antonia and I squeezed through the winterberry bushes, we spotted Mom’s baby-blue junker parked between the trailer and the tall ginkgo tree. We weren’t expecting to see her so soon. Then again, we were never too sure when we’d see Mom, day or night.

“Don’t say anything about the head,” I reminded Antonia as we approached the trailer. Her eyes grew wide, like I’d said the most unbelievable thing she’d ever heard.

“I wasn’t going to.” As if she wasn’t the biggest blabbermouth in the world.

“Well, just remember it,” I said, and shooed her on ahead.

Antonia slumped her chin on her chest and pouted. “I said I wasn’t going to.”

Mom lay on our old, beat-up couch with the faded bird-of-paradise slipcover. A damp washcloth covered her eyes, and her smudged sneakers were still tied tightly on her feet. That meant a bad day at work.

“Hey there, firecrackers,” she said in a gravelly voice, not taking off the washcloth. Antonia knelt on the floor near Mom’s head. She removed her duckling barrette and leaned back so Mom could stroke her fine, straight hair.

It seemed like Antonia got all the best parts from our parents—Mom’s glossy chocolate-brown hair and dark eyes, and Daddy’s high cheekbones—while I ended up with a dirty-blond mess that ate combs, a pug nose, and eyes the color of dishwater.

At least neither one of us ended up with our daddy’s temper. We’d already had our fill of it anyway. Not anymore, though, or at least not in the twelve months since we’d last seen him.

I carefully tucked my bag out of sight at the other end of the couch. Mom raised her feet to let me sit down. I pulled off her sneakers and socks and rubbed her feet.

“Mmm, that feels good, Peppernose,” she said. Mom called me that because of the dark freckles all over my fish-belly-white face. I thought they made me look ugly, but I still liked the name. She only ever used it at home, so it was like our own secret code.

I trailed my finger across the calla lily tattoo that curled along her calf. “Work go okay?” I asked.

Mom shrugged. “It went.”

Antonia and I exchanged a worried look. I hated how tired she sounded after work, and how her clothes always smelled like onions and cheap coffee.

She worked weird hours as a waitress at Theodora’s Hometown Diner. Mornings, evenings, weekends, holidays—there wasn’t a time or a day she wouldn’t be expected to show up. She never talked about her job except to say it was like trying to juggle ten balls while tap-dancing, and every once in a while someone would throw you a watermelon and a bag of cats.

“We were down by the river,” Antonia blurted out. Whenever she gets worried about Mom, she rattles her mouth about random things no one asked her. I shot her a look before she blabbed everything about the doll head. “Oh yeah,” she went on, winking at me, “but we didn’t find anything there.” Like Mom wouldn’t see right through her.

Sure enough, Mom lifted a corner of the washcloth and squinted at Antonia. “What did you find, and where did you put it?” Antonia once brought home a pail full of tadpoles. She’d put them under her bed and promptly forgot about them until a week passed and their death-stink got Mom’s attention.

“Just some skipping stones,” I said quickly, before Antonia could mess things up even more. “She wanted to bring some home, but I made her leave them there.”

That seemed to satisfy Mom. She lowered the washcloth and handed her foot back to me.

“Looking forward to the first day of school tomorrow?” she asked me. Looking forward? Icy fingers dug into my gut.

“Sure,” I lied.

“Keep an eye on your sister as much as you can. Oh, and I called the school today and asked if Antonia could have lunch with you on her first day.”

I squeezed my mom’s foot. She yelped. “Ow, watch it there,” she said.

“Lunch?” The icy fingers curled into a fist. “With me? And all the other seventh graders?”

“Can I sit with you and your friends?” Antonia squealed.

“No!” I shouted, a lot louder than I meant to. Mom lifted the washcloth and stared at me. Antonia pouted. I looked down like I’d suddenly found something interesting under my fingernails. “I mean, why doesn’t she go with the other sixth graders?”

“Lucille Penelope Bloom,” Mom said. I winced. Once she trotted out my full name, I knew I was sunk. “It’s just for one day. You know how flustered Antonia gets with new situations. I don’t think it too much to ask to let her sit with you for a half hour out of the first day of school.”

“It’s forty-two minutes,” I mumbled.

“Fine. Forty-two minutes, then.”

“And she’ll be with me on the bus.”

Mom swung her legs out and took hold of my chin. Not painfully, but firmly. “Are we going to have a problem here?”

Whenever Mom did this, I knew she meant business. Not that she’d ever hurt me, like you saw with some parents. Besides, I never pushed too hard. I just couldn’t do it. I shook my head.

Mom smiled and pulled me into a hug. Antonia squeezed against her on the other side.

“I’m not trying to make things hard for you, Peppernose,” she said. “I just want to make sure both my girls get through middle school without t

oo much trouble. Okay?”

“No trouble on the double,” Antonia said, and giggled.

“Double trouble is right,” Mom said. “Why don’t you two go to your room and see what I got for you to wear for your first day back?”

Antonia gasped. “New clothes?”

Mom sighed. “Well, they were on clearance.” Antonia didn’t care. She bolted off to our room with her howler-monkey yell on full volume.

Mom nudged me with her shoulder. “You too, big sister. Check out what I got for you. I think you’ll like it.”

“No stripes?” I asked.

Mom shook her head and lay back down, covering her eyes with the washcloth. “No stripes. You think I just met you yesterday?”

I started to walk away, then stopped and turned back. The icy fist pounded my gut. Just tell her, I thought. If she knows, maybe she’ll let you stay home. Just for one day. Maybe a week. Or a year.

“Mom?”

“Yeah, Peppernose?”

I opened my mouth to say one thing, then shut it tight and opened it again. “Thanks for the clothes.”

Mom waved a limp hand. “Anything for my firecrackers. Now git.”

* * *

—

I wasn’t two steps into the bedroom when Antonia snatched away my backpack and nearly tore off my arms.

“Watch it!” I complained, but she was already focused on pulling out the doll’s head. Our closet door was open, and it was clear Antonia had been busy setting up a place of honor on top of a cardboard box she’d shoved inside.

“Perfect,” she said, and kissed the doll’s nose as she set it on the box. Then from a corner of our room she dragged a little wooden chair Mom had picked up from a yard sale years ago and set it facing the doll head.

“I don’t think that’s a good idea,” I said. “Mom’s going to find that thing and throw it in the trash. Hide it in the dresser.”

Antonia shook her head. “Can’t.”

“Why not?”

Antonia rolled her eyes. “How can I have conversations with her through the dresser? That’s so rude.” Then she squeezed her behind in the tiny chair built for a much tinier behind than she’d had for some time and shut the closet door. And that, apparently, was the end of that.

Hush-a-Bye

Hush-a-Bye