- Home

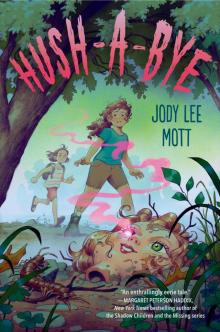

- Jody Lee Mott

Hush-a-Bye Page 2

Hush-a-Bye Read online

Page 2

Later that night, when the lights were out and the covers were pulled over my head, I heard Antonia shuffle out from her bed. She tapped lightly on the closet door and slid it open. And then she whispered a song that sounded kind of familiar.

Hush-a-bye and good night

Till the bright morning light

Takes the sleep from your eyes

Hush-a-bye, baby bright

She sighed, shut the door, and dove back under her covers. It didn’t take long for her teeth to start grinding together. She did it every night, and it sounded like she was chewing on a brick. One of these nights, she was going to grind her teeth down to the gums. It made my own teeth hurt listening to it, but I knew snoring would follow soon enough. It was still annoying, but at least I could sleep through it. But that night, while I waited for her rumbling snore, I heard something else.

“Good night, Lucy, sleep tight.”

I pulled the covers back from my head and looked at Antonia. She’d already stopped grinding and was revving up her snoring. I glanced at the closet door. It was shut tight.

I shivered and pulled the covers back over my head. It didn’t make sense. Antonia was never one to talk in her sleep. But that wasn’t the strangest part. I figured it was just my imagination, but I could have sworn I heard those words coming from inside the closet.

3

“LUCY, LOOK! I think I see one falling. Do you see? Do you see?” Antonia danced about in an early-morning quilt of sunlight and shadow as she strained to look through the branches of the ginkgo tree.

“It’s only the beginning of September.” I shifted my backpack to get a better look. The fan-shaped leaves were still summer green. “Too soon.”

A year ago, when we first moved into the trailer, we discovered the best thing about our new home was the tall ginkgo tree growing next to it. The only trees we’d had at our previous house were a couple of sour-looking crab apples. It had been near the end of October, so Antonia and I had started planning the leaf-pile stunts we’d do once the leaves fell. We waited and waited almost the whole fall for the leaves to drop off the ginkgo tree. As the days and weeks went by, most of the other trees had shed their leaves bit by bit until they were bare as skeletons, but not the ginkgo. Its leaves didn’t budge, not a single one. Not even late in November.

Then, one morning, a few days after the Thanksgiving break, we stumbled out of our trailer to catch the school bus and discovered a neat circle of leaves around the trunk of the ginkgo. Its branches were completely bare. Somehow, they’d all fallen off overnight at exactly the same time.

This year, I hoped we’d get lucky and they’d all drop right when we looking at it. But it was the first day back to school, so I didn’t feel particularly lucky about anything.

I tugged on the strap of Antonia’s bulging backpack, the pink kitten one she’d had since third grade.

“The bus’ll be coming,” I said. “I don’t want to be late.”

Antonia moaned, then tromped on toward the stop. I could see her straps were getting so frayed, I wondered if they’d hold. It looked like she’d jammed in several of her precious treasures along with her school supplies. As long as she didn’t bring the doll’s head. That would be a step too far into Weirdville, even for Antonia.

Despite my warnings that morning, the duckling barrette still clung stubbornly to her head. She may as well have worn a KICK ME sign. I wanted to be her protector, but my qualifications for that job were pretty thin. She’d be on her own in middle school. The barrette was not a good start. I know it sounds mean, but sometimes I wished her brain was wired better.

Even worse, there were some days I wished I didn’t even have a sister.

Our bus stop was the second one on the route. So, like always, I grabbed the safe seat right behind the bus driver. Antonia jammed herself next to me, but I didn’t mind. She didn’t know it, but she was helping me. With her there, I could sit by the window and not worry about who might plop next to me.

The icy fingers in my belly unclenched a little. Antonia slipped her backpack to the floor and craned her neck over the seat to spy down the back of the bus.

“This doesn’t look any different from my old bus,” she said, sounding a little disappointed.

“All buses are the same,” I said in a quiet voice.

“What?” Antonia shouted, and whipped her head about. On the opposite seat, a sliver-thin blond boy with a finger halfway up his nose squinched his eyes at her. I rapped Antonia’s thigh with the back of my hand.

“Stop yelling,” I whispered.

Antonia shot me a puzzled look, then folded her arms and slumped in her seat. “I thought it was going to be bigger.”

The next two minutes passed quietly. The only sounds were the rumble of the bus, the wheezy breathing of the little blond boy, and Antonia picking her teeth with her thumb.

Two whole minutes.

I tried to lose myself in those minutes, like it was the last piece of time left in the world. If I ever got to heaven, and it turned out to be nothing more than a rattling bus ride with a skinny nose picker and my sister sucking at her teeth over and over again for eternity, I’d be okay with that.

But happiness would have to wait. I was heading to middle school.

Once the bus cleared the trailer park, the houses grew bigger, the evenly mowed lawns gleamed greener, and the number of rust-bucket cars like ours dwindled considerably.

Soon the bus squealed to halt, the door whooshed open, and a noisy pack of kids piled on. They all walked past Antonia and me. Most ignored us. A few made faces. None of them said hello. Neither did I.

Antonia didn’t seem to notice or care. She was too busy petting the red panda on her shirt. But then Gus Albero, a big lump of a boy who was always tearing up the streets on his dirt bike, thumped up the bus steps. His weasel-faced friend Zoogie slinked and snickered close behind. He gave Gus a hard shove, and Gus, not expecting it, lost his balance and tipped forward. His hands slammed hard against the corner of our seat, and the vibrations shot straight up through my spine.

I stopped breathing and waited. Please, please, please, please go away, my brain pleaded. My body did nothing at all. Like usual.

But not Antonia. She shoved Gus back with both hands. “Watch out, jerk!” she said.

Gus stared at her for a second like he couldn’t figure out what spaceship she’d just beamed down from. Then he snorted and said, “Smell you later.” But he still backed off.

Now it was my turn to stare at Antonia. I couldn’t believe how easily she’d done that. Most of the time I was embarrassed how Antonia “had her filters off,” like Mom would say. She’d just blurt out whatever rolled through her brain at any given moment, usually the worst possible one. Like the time in the grocery store parking lot when Antonia gawked at a very large woman with low-riding pants wrestle a fifty-pound bag of dog food into the back of her VW Bug.

“Mom,” she’d said in a shout you could hear halfway across the lot, “you see that lady showing her big butt? I bet you could stick a couple of quarters in there like a gumball machine.”

I’d never known my mom’s face could turn that shade of red.

But this was different. The way Antonia handled Gus was excellent. Maybe the day wouldn’t be so bad after all. Maybe having Antonia act as a buffer at lunch could actually work. She’d say all the things I never dared to say.

The icy fingers wiggled free a little. I may have even smiled.

Then the bus jerked to stop at the corner of Main and Little, and the bus doors whooshed open once again. A pair of hard heels click-click-clicked up the steps. A whiff of cherry and cinnamon tickled the air.

My smile, if it ever was there, vanished.

Madison Underwood appeared, filling the aisle like a rolling thunderhead. And those icy fingers reached up through my throat, clamped on my brain,

and dragged it down to my stomach.

Madison—Maddie to her friends—was as flashy and polished as a new bicycle. Her rosy skin, straight white teeth, and glossy nails gleamed, and her smooth black hair flowed easily over her shoulders. Everyone looked at her, including me, and she knew it. Her eyes soaked up all the adoration.

But when those copper-brown eyes found mine, the pleasure drained away, and all that was left was pure poison. All for me.

“Keep moving there, honey,” the bus driver said. Madison gave me a half second’s worth of eye venom, then turned to the bus driver and smiled.

“Sorry, Mrs. Hamish,” Madison said in her sugary, finger-wrapping voice. Mrs. Hamish, like every other adult, returned her smile. Madison breezed down the aisle, followed by her giggling twin minions, Ashley and Gretta Oslo.

As the trio passed, I let out the breath I’d been holding. It was over. The worst moment of the morning bus ride, the one I’d been dreading and trying not to think about was over. There’d be other bad moments waiting for me at school, but at least I could check this one off the list.

That’s what I told myself. And like usual, I was wrong.

“Wow, she’s pretty as a lollipop,” Antonia said. Very loudly.

I stiffened, feeling the scorch of Madison’s stare as she took in the loud girl with the sparkly duckling barrette and the clearance-aisle red-panda shirt. The one sitting next to me.

“Hi, I’m Antonia,” my sister continued, answering a question no one had asked. “I’m Lucy’s sister.”

My throat clenched tight. I wanted to reach out and grab Antonia by the neck and shake her until her brains rattled, screaming Shut up! Shut up! I couldn’t have done it, though. In fact, that would be breaking the first and most important of my Middle School Survival Rules. Rule Number One: Never speak to anyone except adults, and then only if they ask you a direct question. The Rules could never be broken, no matter what.

I heard a snort and a breathy laugh, and then Madison’s heels clicked away down the aisle. A comment followed them just loud enough for me and the adoring crowd in the back seats.

“Did you see the fish eyes on Trash Licker Junior?” The back-seat crowd let loose with a laugh particular to middle schoolers, the kind that could strip the paint from concrete.

Antonia shook my elbow. “Why is everybody laughing?” she asked. “Who’s Trash Licker Junior?”

I didn’t answer her, even when she started pinching my arm. My eyes had closed. It wasn’t perfectly black behind my lids because of the dancing sunspots, but it would do. If I couldn’t see the world, then the world couldn’t see me either.

I knew it was stupid and childish. But for a few moments, I pretended I was all alone in the world—no other kids, no school, and especially no Antonia. It didn’t matter if in about fifteen minutes I’d have to open my eyes again with the whole rotten year ahead of me. For fifteen minutes, I could pretend none of that mattered.

So while Antonia poked and prodded at me, asking me to explain what was so funny, I shut down and disappeared. That’s what I did best.

4

“LOOK AT ALL this,” Antonia said, gawking at the cafeteria like it was the Grand Canyon. Her pink kitten backpack was still overloaded and slung pointlessly on her shoulder. I wondered if she’d taken it off since the morning. Her eyes darted in every direction, and she swiveled her head back and forth like an automatic sprinkler. “This is way bigger than my old school.”

Somehow, I’d managed to get through the morning classes without anyone really noticing or caring I was there. I’d snagged Antonia as she spilled out of her reading intensive and dragged her to the cafeteria before too much of a line formed. Only seven kids in front of us. I closed my eyes and breathed.

4576, 4576, 4576, I kept repeating in my head. My lunch ID number, the one I’d need to punch into the keypad to pay for my meal, was the same one I’d had last year. But I wasn’t taking any chances.

“Do we have an assigned table? Can we sit where we want? Do they have pepperoni pizza?” The questions tumbled out faster than I could handle. Not that I tried to give Antonia any answers. I just grabbed a tray for her and one for myself and slid mine along the metal bars.

Now only four stood in line ahead of us. A damp hamburger and a dish of slightly green tater tots cowered miserably on my tray. The smell of floor cleaner and grease left over from 1964 combined into some unnatural fumes. More than likely it caused brain damage, which would explain a lot about middle school.

Antonia was still jabbering away about something or other. I figured if I at least got us to the lunch table, she could jabber on all she wanted. I’d make an excuse later about why no one sat with us, why my eyes stayed locked on my tray and never looked up except to check the slowest clock in the world, and why I never said a word to anyone.

4576, 4576, take one hamburger, one dish of tater tots, one dish of peas, one milk, one fork, one napkin, punch in the number, walk to the round table, sit, eat, wait, 4576, 4576—

I had the drill down cold. In five minutes, we’d sit down. After thirty-seven more, lunch would finally be over—sometimes eaten, sometimes not. I usually felt less queasy when it wasn’t. Ninety-four minutes after that, the school day would end. Twenty-five minutes later, we’d hear the whoosh of the bus doors close behind us. And sixteen hours later, the whole ordeal would start all over again.

Whoopee.

4576, 4576, 4576—

Antonia tugged at my sleeve. “Lucy, Lucy, Lucy,” she chanted in her much-too-loud voice, “which one’s our table, huh? Tell me! Where do you and your friends sit?”

“Friends?” a familiar voice said from farther down the lunch line. “What friends?”

No, no, no, please no. I didn’t have to turn around to recognize Madison’s snarl. The snorting noises that followed every nasty word she spat out had to be Ashley and Gretta. I tried not to listen, but the words still found me and drilled right into my brain.

“Who’d want to be friends with Trash Licker? She smells like cat puke.”

“Oh, Maddie! You’re so mean!”

“Soooo mean!”

I peeked a glance at Antonia to see how she was taking this, but she was oblivious. Fine by me. The icy fingers, though, were squeezing the breath out of my lungs.

4576, 4576, 4576, please, please—

“It’s true. Even bug-eyed Trash Licker Junior smells like it. That’s because cat puke’s all they can find at the dump.”

“The dump? Gross!”

“Ew!”

Shut up, shut up, 4576, 4576, 4576—

Only one person ahead of us. All I had to do was punch in the lunch code and I’d be set. Madison and her followers always clustered near the long row of windows, far, far away from my table. She could trash-talk me all she wanted from there. We wouldn’t hear a word of it. Even so, the icy fingers squeezed harder and harder with every breath I sucked in.

4576, 4576, 4576—

“They go there every night for dinner. Eating cat puke and rat heads.”

“No! Gross! You don’t mean for real. Is that for real?”

“Ew!”

Finally, I reached the register. A sharp pain stabbed between my eyes. Everything was blurry. My shaking fingers paused before the keypad.

Okay, okay, 4756, 4756 . . .

My heart skipped a beat. Wait. Were those the right numbers? Is it 456—no, 47—no, what is it—what is it—

“Put them in already.” The lunch lady at the cash register, new to me, wore too much makeup and looked bored. MRS. DUDLEY was scrawled on her name tag in Magic Marker.

My fingers couldn’t stop shaking. Those four numbers, the same ones I’d been punching in day after day for a whole year, had suddenly dissolved.

“Put them in already,” Madison mocked in a high voice. The twins snickered.

“Yo

u want me to do it?” Antonia asked. She reached over and banged keypad buttons at random.

“Stop that,” Mrs. Dudley snapped. She grabbed Antonia by the wrist and swung it away. “You’re holding up the line. If you don’t know your credit code, lunch is three dollars and forty-five cents.”

“Nuh-uh,” Antonia said, blowing on her wrist. “Not for us. We don’t have to pay anything. We get our lunch for free.”

Mrs. Dudley raised her eyebrows. Laughter ran down the line. And the icy fingers reached up and grabbed me by the throat.

We’d been on the free lunch program since arriving at Oneega Valley because Mom’s pay was so low. So were a quarter of the kids in the school. But no one bragged about it. No one ever talked about it. Because if you let a certain kind of person know you’re poor, they can turn mean. Ugly mean.

“Hear that?” Mrs. Dudley said over her shoulder in a very loud voice. “She gets her lunch for free.”

Two beady eyes and a hairnet appeared in a small window behind Mrs. Dudley. They disappeared for a moment, then popped back into view.

“She’s 4576,” a husky voice growled from the back. “And her sister’s 3827.” I banged the numbers in frantically one after the other and took my tray from the lunch line. I hoped Antonia was following me, but I didn’t dare look.

“Think they don’t have to pay for nothing,” Mrs. Dudley grumbled as I slunk away. “Maybe somebody at home should try working for a change.”

My hands shook even after I sat down at the round table. Antonia, who thankfully had followed after all, set down her tray next to me. She didn’t sit, though. She remained standing with her head tilted to one side, staring back at the lunch line.

“Why’d that lady say that?” she asked.

“Sit down,” I whispered.

“But why’d she say that?”

“Please sit down,” I whispered again, as loud as I dared. Antonia finally sat, but her eyes never left the lunch line.

Hush-a-Bye

Hush-a-Bye